I`ve recently got back from two weeks in Japan. It`d been a full year since I`d come back to the UK and I was really interested to see what it would feel like being back there. After all, Japan is now a second home to me.

Except it didn`t feel like it.

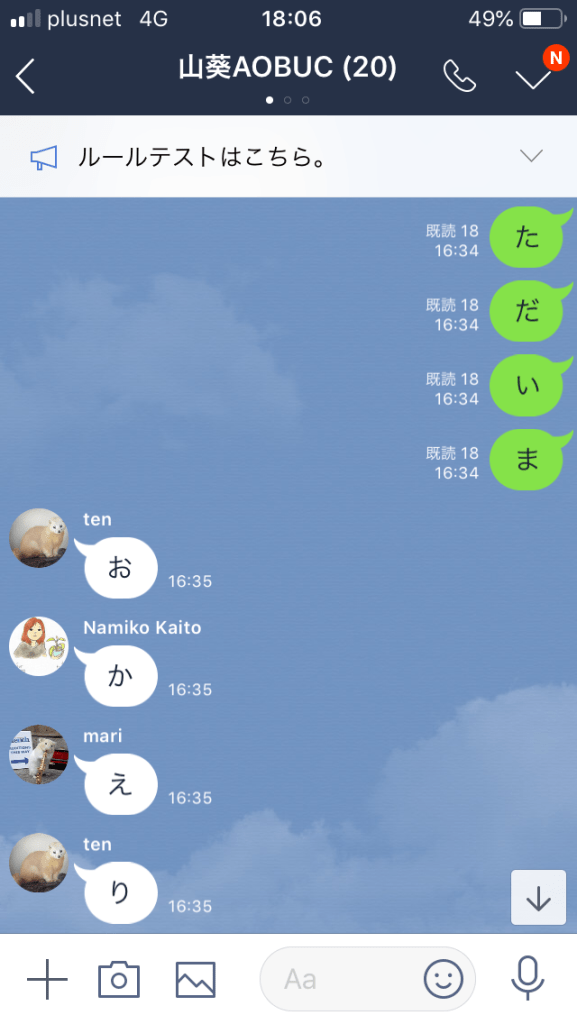

I was hoping/expecting I`d experience a strong sense of tadaima when I arrived back. “Tadaima” being the set greeting for when you return home after a day at the office, etc. In English it`d translate as something like, “I`m back” or “I`m home.”

I had played with the idea of greeting the customs desk with “tadaima.” But coming through the airport I didn’t feel any sense of arriving home. I was, to be fair, quite tired at that point, arriving into Tokyo about midnight after a day and a half of travelling, so I wasn`t sensing much of anything beyond jet lag.

As I waited for the train from the airport I treated myself to a can of Royal Milk Tea from the vending machine. Refreshing to be sure, but no tadaima experience.

Coming into Tokyo was fun and felt very natsukashi (`nostalgic`-ish) but still no sense of tadaima. One mad luggage-hauling dash through Shinagawa staion to catch the final train of the night (with a full seven seconds to spare!) and I was walking through the familiar streets of Ichikawa.

The next morning I went to the nearby Lawson to grab some breakfast. That felt really familiar: foods that I remembered in places that I remembered them being. Familiar . . . but not home.

It took me a little bit of time to get back into the flow of speaking Japanese. I`ve had a few opportunities to speak Japanese back in the UK but very spread apart and only for a couple of hours at a time. A few days of speaking non-stop Japanese was a bit of a shock to the system at first, and a nice combination with the jet lag, but I got comfortable with it after that.

I feel at ease in Japan, but not at home.

And I think that`s OK. Because Japan isn`t my home. And no matter how fluent I get at Japanese, it won`t change the fact that I am a foreigner in Japan. I wasn’t born or raised here. My parents aren’t from here. Japan doesn’t feel like home, and it probably never will.

But then I went to training with my frisbee team mates. And after that I had a prayer meeting with the kanto OMF folk, followed by catching up with a Japanese friend, and I start to realise . . .

Tadaima isn`t something you feel yourself, it`s something you say to people, and it doesn`t work without someone to respond with an okaeri (“welcome back”). Although “tadaima” is best translated as “I`m home, ” it isn`t really about arriving at your house, it`s about being with your family.

Missionaries – and others who spend time living overseas – often speak about living without knowing where `home` is. And missionary kids (or in my case, army kids) struggle with how to answer, “Where are you from?” I was born in Germany, spent my childhood years in the south of England, my teen years in the north, and now I`m preparing to return to Japan for a second four-year stint. Committing to serve the church in Japan long-term has left me without somewhere to call home in the strict sense of the word. But in return I`ve been blessed with family – in the UK, in Japan, and indeed all over the world.

I don’t own a house in Japan, and it`s tough to even rent a place as a foreigner (especially one on a `religious` visa). There`s always going to be the red tape and the language and culture barrier will never fully go away. But for all the reminders that I`m not from Japan, I have friends who assure me that I am welcome there. Their cheerful call of “okaeri” is what finally gives me that sense of tadaima, so whilst Japan doesn’t feel like home, it does feel like family.